As a way to get my own blog restarted, I thought I would post this great piece on peer reviewers from Scientist Sees Squirrel

Category Archives: Uncategorized

Deextinction: Asking the Wrong Question

The phenomenal ecological success of humans and our cadre of partner species (livestock, crops, pets, parasites) has come at great cost to other species. Indeed, one of the hallmarks of the Anthropocene is the sixth mass extinction event, one that is shaping up to be on the order of the End-Cretaceous event that took out the non-avian dinosaurs. Our list of victims includes almost all of the non-dinosaur poster species for extinction: Wooly Mammoths*, Tasmanian “Tigers” (really marsupials), Dodos, Passenger Pigeons, maybe even our close cousins the Neanderthals*. And despite our conservation efforts and good intentions, the Anthopocene extinction event goes on, fueled by human population growth, our monopolization of natural resources (land, plant productivity, fisheries, etc.), and increasingly, anthropogenic climate change.

This is tragic, but understandable. Earth is finite, the vanishingly thin skin of its Biosphere even more so. As we take more and more, there is less and less to go around. At a very coarse level, the math is remarkably simple, and sad.

Wouldn’t it be great if we could bring them back; if through human ingenuity, hard-won technical know-how, and forward-thinking venture capital investment, we could revivify extinct species? Imagine the crowds of conservationists, dabbing tears from their eyes as the first new flock of Passenger Pigeons is released. Imagine yourself on a Siberian safari, trekking over the remnants of soggy, melting tundra to observe a newly established herd of Wooly Mammoths. Wouldn’t that be great?

That is the vision of “deextinction,” and it is not science fiction. It is a very real endeavor being pursued by a collection of scientists and conservationists. The biotech basics of the process have already been worked out and several projects are up and running, including goals of producing a viable cloned Wooly Mammoth and a new Passenger Pigeon. Last week’s TEDxDeextinction Event was a debutante ball for the project. For a taste, you can watch Stewart Brand’s talk, entitled “The dawn of deextinction: are you ready?”

It may surprise you to know that as an ecologist I would say, emphatically, NO (and I am not alone). Don’t get me wrong, I would LOVE to see a flock of passenger pigeons or a herd of mammoths as much as the next nature geek. And I marvel at the scientific insights and creativity that go into the deextinction project. These people are visionary, brilliant. But Brand’s title asks the wrong question. It does not matter whether we, as individuals, are ready. Instead, I would argue that what really matters is that we, collectively, as the stumbling architects of a new geological epoch, are not ready for this responsibility. Moreover, Earth and its Biosphere are not ready. Developing my argument would go well beyond a blog post, but the summary is rather simple.

Every species is part of a larger ecosystem. This is the fundamental fact of ecology. Many, perhaps even most extinct species belonged to ecosystems that were either coopted by humans, or have changed irreversibly in their absence. The forest/grassland mosaic that was home to the Aurochs (another deextinction target) across Europe is now home to some of the densest human populations on Earth. The world of the Aurochs is gone. The glaciated home of the Mammoth is gone, and we are marching in the opposite direction, climate-wise. The world is not ready for them to come back. Every revived species would need to have a place, and yet, we cannot even seem to make room for the species that are still here. If we cannot responsibly manage the extant species, do we really want to take on reviving extinct ones? I argue that we are simply not ready, not competent enough as a species to handle this task.

I have no illusions. Some form of deextinction will occur, with sad solitary animals, maybe even small populations consigned to zoos and reserves. And I have no doubt that the projects that lead to these breakthroughs will yield tremendous insights, both technical and conceptual. Some of those insights might even help rescue extant threatened species.

And that would be great.

But my fear is that news of these big ideas, of this optimistic, technologically advanced project will be interpreted as a solution to the biodiversity crisis. No need to worry about Tarzan’s Chameleon, the Spoon-billed Sandpiper, the Pygmy Three-toed Sloth, or any of the other 100 most threatened species. Just freeze some DNA, and we’ll bring them back later.

Species need space and food, a functioning ecosystem, not just a genome and a zoo. Perhaps the visionaries of deextinction have fallen prey to the most common form of hubris in science, solving the problem of how they can do it without thinking deeply enough about the questions of why or whether they should do it.

What do you think?

*The role of humans in the extinction of Pleistocene megafauna and the nature of our interactions with Neanderthals are still subject to investigation. But while correlation is certainly not causation, extinction, particularly of large vertebrates, does seem to have followed in the wake of the migrations of evolutionarily modern humans, whether in Eurasia, Australia, Oceania, or the Americas.

IBS, part 3: The Anthropocene: Biogeography from the Far Future

At a scientific meeting like the IBS, most of the presentations detail specific, narrowly focused studies, the bricks and mortar of the scientific edifice. But sometimes there are fora in which we get to explore BIG IDEAS. One of the Saturday sessions at the IBS meeting delved into an important recent big idea by examining The Biogeography of the Anthropocene.

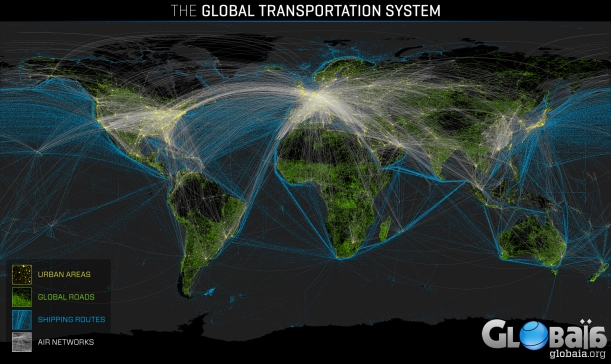

So what’s the big idea? The Anthropocene. It has been proposed as a new geological epoch reflecting the emergence of humanity as a global force of nature, on a par with the other phenomena that shape the planet, things like asteroid impacts, glacial cycles, massive volcanism, and plate tectonics. You get the idea if you take a look at our global transportation system. We are big.

But what is the evidence for the dawning of the Anthropocene? That was the topic of the first talk of the session, by Tony Barnosky from UC Berkeley. For you see, the Anthropocene is an epoch that does not yet officially exist. It is being considered by the International Commission on Stratigraphy, which, after careful consideration, will deliver a verdict on the status of the Anthropocene in 2016. Barnosky is part of the working group doing that careful consideration.

What was most interesting for me was that Barnosky’s talk was not about the abundant current evidence for human impact, but about how those stalwart stratigraphers would go about delineating the boundary of the Anthropocene. He emphasized that while we think of epochs as periods of time, and thus ultimately intangible, they are in fact defined by the most tangible of earthly things: rocks. Each age in the geological time scale corresponds to specific rock strata deposited during that period in Earth’s vast history, and the boundaries of the period must be clearly defined by globally observable stratigraphic zones. In particular, biostratigraphic zones, delineating particular changes in fossil assemblages, have been instrumental in defining distinct geological epochs. And like any other epoch, the Anthropocene requires a stratigraphic definition.

Listening to Barnosky, I imagined a time far in the future, tens of millions of years after the last human passed away, our species extinct, a ghost glimpsed in fossils, artifacts, and fragmented, indecipherable texts and codes. If some newly sentient and scientific creature were to arise on Earth (or, if you prefer, arrive on a spaceship) equipped with rock hammers and microscopes, how would they recognize the fact that a single species of (at least semi-) intelligent primate had come to dominate the biosphere and change the planet?

According to Barnosky, ample fossil evidence will point to big biogeographic and biogeochemical changes centered around our present geological instant (mid to late 20th century). For example, one future paleontologist, a specialist in fossil seeds, will note not only a global proliferation of maize seeds out of what was once North America, but also a synchronous differentiation of many new forms in the lineage, like the super sweet varieties we enjoy every summer here in Ohio. Another paleobotanist will note that in the same strata, so many newly introduced plant species appear in Australian fossil assemblages that they come to outnumber the previously recorded native species in a geological instant. In a separate publication, an invertebrate paleontologist will observe over the same period a global homogenization of marine fossils, transported worldwide by our shipping fleets. Bivalves isolated to the western Pacific in earlier strata will appear in north Atlantic deposits or on the coasts of the Indian Ocean. The title of her paper might be “Suddenly, everything is everywhere.” Another rock hound will note that in many marine deposits, this change in the invertebrate assemblage is associated with another sort of biostratigraphic zone, a horizon of microscopic shards of plastic, as dazzling in its array of colors and chemical composition as it is notable for its depth. The flattened remnants of our settlements and road networks, even the radioactive traces of our flirtations with nuclear power and nuclear weapons, all of these stratigraphic features will coincide. Slowly, those strange and wonderful new scientists will piece together a story, chronicling the biological evolution, cultural emergence, and perhaps inevitable decline of our species, the authors of our own geological epoch.

But as I listened to Barnosky’s presentation, I started to wonder not about the strata at the base of the Anthropocene, which he seeks to define its beginning, but about those layers of rock yet to be laid down. What story will they tell of humanity after its global emergence? Will they document a cataclysm of geological upheaval and mass extinction, like those that followed the Great Oxygenation Event or the Chicxulub impact? Or will those layers tell a new story, one never before seen in the history of life on Earth, of a species that sought to mitigate its newfound global impact in order to maintain a sustainable planet? What will those future paleontologists read of our own future?

Recognizing the Anthropocene is a sort of coming-of-age for our species, an acknowledgement that we can no longer live as simple children of nature, grabbing what we need or desire and discharging our waste without regard for our impact on the rest of the planet. More than just a new box on the geologic time scale, it is a first step towards “putting away childish things” and taking responsibility for our collective actions. We have a choice, and the future is watching.

One of the realities of rapid climate change is that environmental conditions are changing so fast that many species cannot migrate or adapt quickly enough to keep up with them. This problem is especially present for some of my favorite organisms: trees. Trees, of course, can only move as seeds and their generally long generation times mean that evolution moves at the pace of, well, a tree.

This problem has many ecologists and conservation biologists considering rather extreme measures: helping organisms move around to keep up with climate change. Of course, this sort of action has risks involved, so there is a robust debate going on in scientific and management circles. This post, from the Early Career Ecologists blog, does a great job of laying out the basics of assisted migration.

Trees on the move?! I know you’re thinking, “Come on, Sarah. Trees can’t move.” And, generally, you would be correct in that statement. Tree species are now, however, in a position where movement may be necessary for survival under changing climatic conditions. How trees will move is under debate within the ecological community, but why trees will move is accepted as a survival strategy related to the adaptation of species.

View original post 1,697 more words

IBS Meeting, part 2: A Big Question

One of the exciting things about scientific conferences like the International Biogeography Society meeting is that you get exposed to some Big Questions. On my first day at the meeting, I heard a new one.

What are the gifts you can give your readers?

I almost missed the question. It slipped into the workshop like a hummingbird, zipping in between our discussions of How to Expand Your Ideas and Choosing and Using Models of Scientific Writing. The conversation was lively enough that we didn’t stop to answer the question directly, but it hovered in my mind for the rest of the afternoon, buzzing and iridescent.

I almost missed the question. It slipped into the workshop like a hummingbird, zipping in between our discussions of How to Expand Your Ideas and Choosing and Using Models of Scientific Writing. The conversation was lively enough that we didn’t stop to answer the question directly, but it hovered in my mind for the rest of the afternoon, buzzing and iridescent.

The question came from Dr. Sarah Perrault, the leader of our workshop on Writing Popular Science. She guided us through an afternoon that mixed active writing with more reflective discussions of the components of various genres, the need to engage their readers in relationships of trust and credibility, and the balance of facts, values, and actions in our narrative ambitions. But in some ways what it all came down to for me was that single passing question.

I thought about Sarah’s question some more on the way back to my hotel. The walk is a little long (North Miami is built for cars, not pedestrians) but on the way to Biscayne Boulevard, the route cuts through the East Arch Creek Environmental Preserve, a small tangle of woodland and brackish estuaries squeezed in between the Florida International University Biscayne Bay campus and the high rise condominiums that line the bay itself. Walking among the canopies of Australian pine and Brazilian pepper, it struck me that much like the human component of the city, the plants of the preserve are a community of immigrants. These species have tagged along with us humans, transported here from the far sides of the planet. In particular, we planted Australian pine to stabilize beaches and estruary banks, because it is very salt tolerant and forms dense thickets. Unfortunately, like many of our fellow travelers, it has become invasive, displacing large numbers of native species, the collateral damage of our own species’ success.

The Australian pine, Casuarina equisetifolia, is actually not a pine at all. It is not even a conifer. What appear to be evergreen needles are actually small green twigs bearing rings of tiny leaves that fall off during dry periods. Even its fruits look superficially like pinecones, but on closer inspection they actually reflect its closer relationship with flowering plant species in the birch family like ironwood, alder, and hornbeam. Until we humans began transporting it around the world, the Casuarina family was found only in Southeast Asia, India, and Australia, a distribution that reflects its origin on the ancient southern continent of Gondwanaland, sometime around 40-55 million years ago, based on the earliest fossils of those distinctive needle-like twigs and cone-like fruits.

This global re-shuffling of plants (and animals too) signals the emergence of humanity as a geological force, reshaping Earth’s biosphere, atmosphere, and climate in unprecedented and clearly documented ways. Our network of shipping lanes, air traffic, railways, and roads, many of which converge here in Miami, has fostered what biogeographers call a “biotic interchange.” Earlier interchanges include the joining of the Americas by the isthmus of Panama about 3 million years ago. Among many other changes, this event, known as the Great American Interchange, brought hummingbirds into North America for the first time. But our current Global Human Interchange dwarfs all previous events, both in its speed and its extent. Its effects are all around us but often unnoticed, from the zebra mussels choking out the native invertebrates of the Great Lakes to the Casuarina woodlands of the East Arch Creek Environmental Preserve.

Ecology, evolution, and biogeography are sciences of connection, illuminating networks of interactions between species and their environments and tracing those interactions through lineages of descent deep into Earth’s history. This view of life transforms and brightens reality. The tree passed on the trail is no longer just a tree, it’s part of a larger story, a story that ties the present streets of North Miami to the ancient shores of Gondwanaland.

Scientists learn to read these stories through careful observation, measurement, reasoning, and analysis, and they are edited, revised, critiqued, and rewritten collectively via the scientific literature and at conferences like the IBS meeting.

These stories, sometimes complicated, often beautiful, never ending, are the gifts I hope to share with you.

My instructor, Sarah Perrault, is an Assistant Professor in the University Writing Program and an affiliated faculty member with the John Muir Institute of the Environment at UC Davis. Her book on writing about science for general audiences, Communicating Popular Science, is under contract with Palgrave Macmillan. Having taken this workshop with her, I look forward to reading it.

In the writing workshop we also discussed the fact that many press articles about science are actually ghostwritten by writers working in university public affairs offices, because journalists simply attach their bylines to institutional press releases with minimal editing. So, in the spirit of Jonah Lehrer, I just “borrowed” most of Sarah’s blurb above from the conference website (except for the last sentence). Thanks again, Sarah!

What is Biogeocoenosis?

“Biogeocoenosis” describes the intimate association (coenosis) between living things (bio) and the physical environment (geo): think of it like an ecosystem. The mission of biogeocoenosis (the blog) is to explore these associations in the broadest terms and to make the science behind ecological understanding as intellectually accessible as possible. I chose this name because it is a relatively archaic scientific term (so it was available as a domain name), because it is simply a wonderful word (I love words), and because it sounds like a disease, the primary symptoms of which are an incurable desire to know something about Life and Earth. I have this disease (fatal I fear), and I hope to infect you as well.

Scientific insights will be the main focus of the content, but “broadest terms” means including the philosophical, cultural, economic, and artistic interactions that humans share as part of the global biogeocoenosis. One of the main insights of ecology is that “everything is connected,” so the discussion, like evolution, can go in any number of directions.

So who’s the blogger? I am an ecologist and a Professor of Biology and Mathematics at a small liberal arts college in the Great Lakes region of the United States. I study how climate impacts the distribution, diversity, and interactions of living things, especially trees and insects.